Classification of Singularities

The portion \begin{eqnarray}\label{principal} \frac{b_1}{z-z_0}+\frac{b_2}{(z-z_0)^2}+\frac{b_3}{(z-z_0)^3}+\cdots \end{eqnarray} of the Laurent series, involving negative powers of $z - z_0,$ is called the principal part of $f$ at $z_0.$ The coefficient $b_1$ in equation (\ref{principal}), turns out to play a very special role in complex analysis. It is given a special name: the residue of the function $f(z).$ In this section we will focus on the principal part to identify the isolated singular point $z_0$ as one of three special types.

Poles

If the principal part of $f$ at $z_0$ contains at least one nonzero term but the number of such terms is only finite, then there exists a integer $m \geq 1$ such that $$b_m\neq 0 \quad\text{and} \quad b_{k}=0\quad \text{for}\quad k\gt m.$$ In this case, the isolated singular point $z_0$ is called a pole of order $m.$ A pole of order $m = 1$ is usually referred to as a simple pole.

Examples

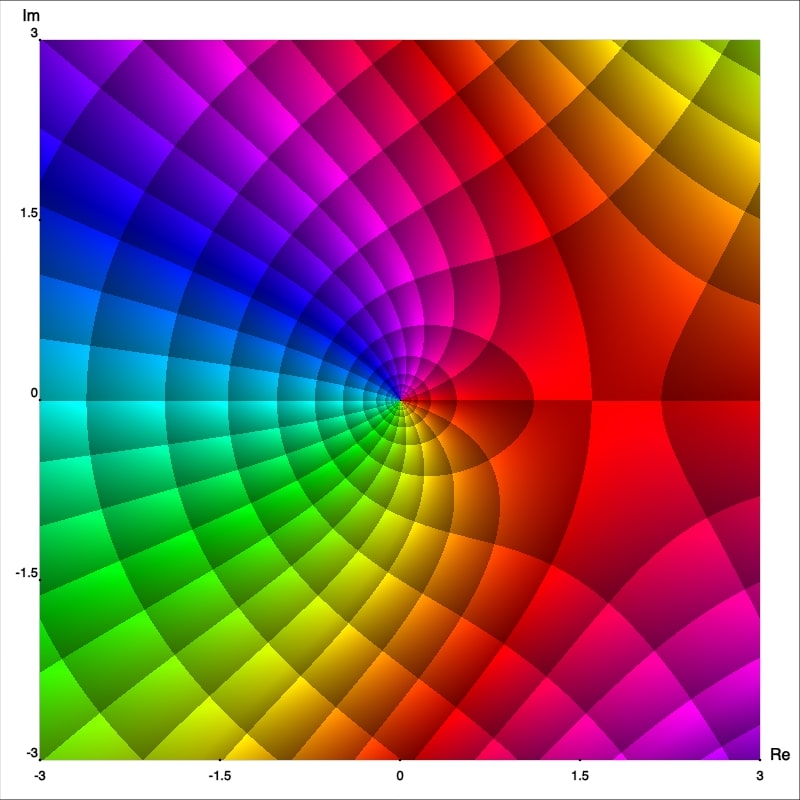

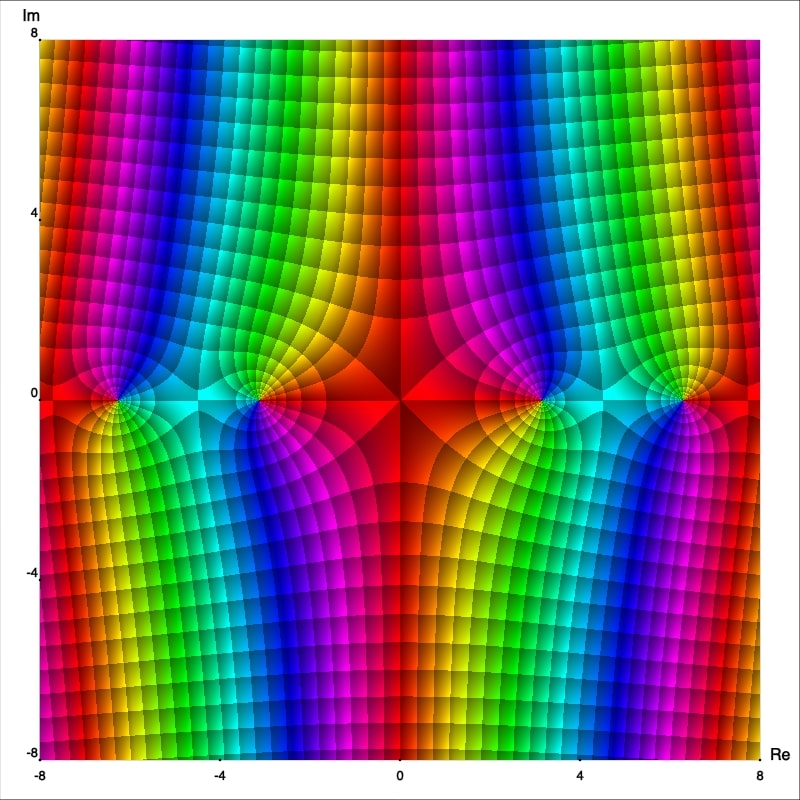

Consider the functions

Now from the enhanced phase portraits we can observe that $z_0=0$ is in fact a pole which order can also be easily seen, it is just the number of isochromatic rays of one (arbitrarily chosen) color which meet at that point. Thus we can claim that $f,$ $g$ and $h$ have poles of order 1, 2 and 3; respectively. To confirm this let's calculate the Laurent series representation centered at $0.$ First observe that

Removable singularity

When every $b_n$ is zero, so that

Examples

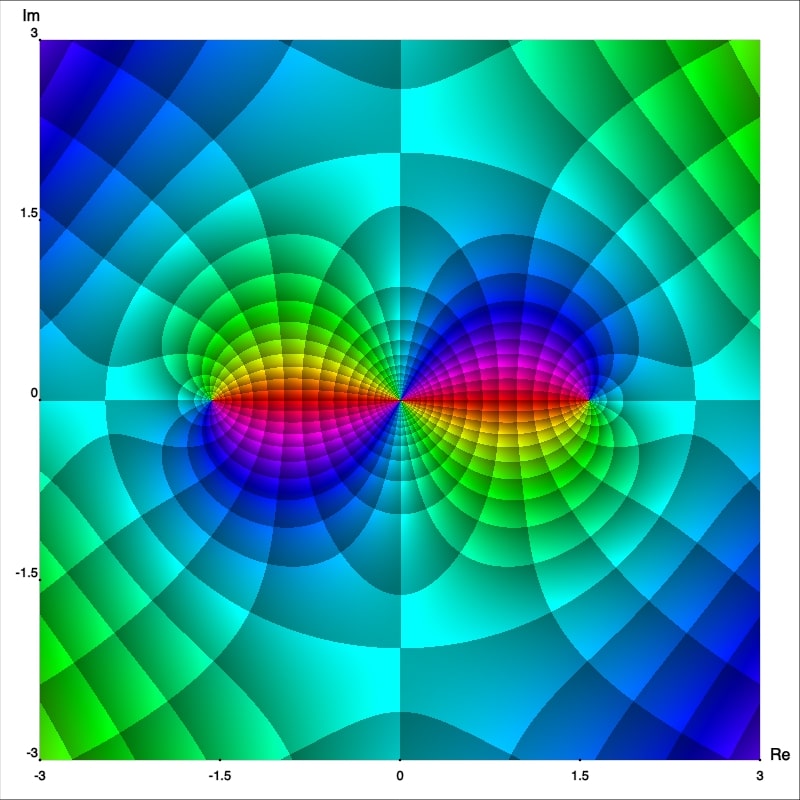

Consider the functions

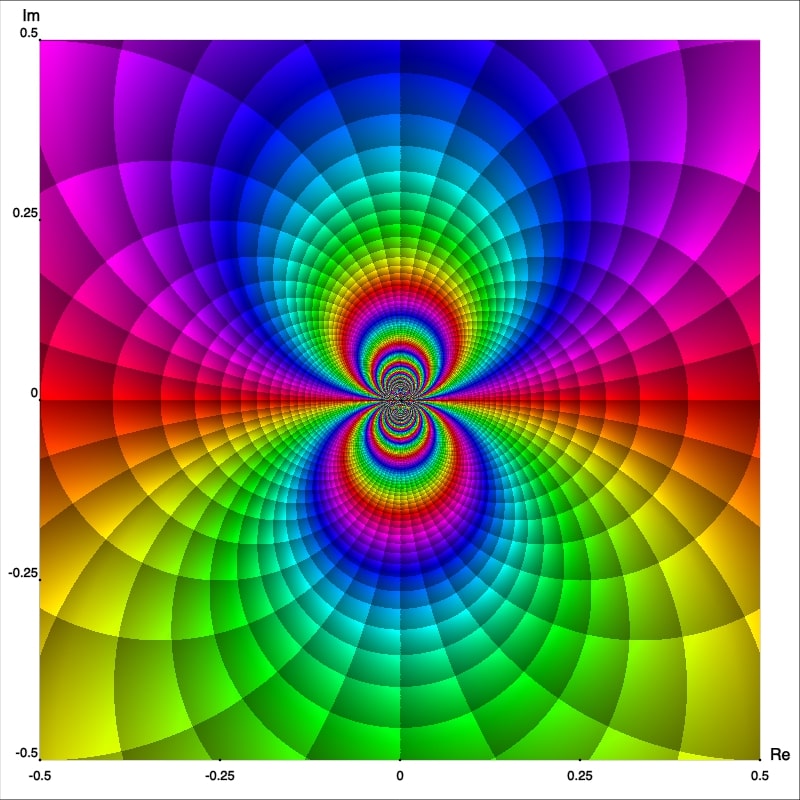

We notice that $f$ has a singularity at $z_0=0$ but in this case the plot does not show isochromatic lines meeting at that point. This indicates that the singularity might be removable.

We can confirm this claim easily from the Laurent series representation: \begin{eqnarray*} f(z)&=&\frac{1}{z^2}\left[1-\left(1-\frac{z^2}{2!}+\frac{z^4}{4!}-\frac{z^6}{6!}+\cdots \right)\right]\\ &=&\frac{1}{2!}-\frac{z^2}{4!}+\frac{z^4}{6!}-\cdots, \quad (0\lt |z|\lt \infty). \end{eqnarray*} In this case, when the value $f(0)=1/2$ is assigned, $f$ becomes entire. Furthermore, we can intuitively observe that since $z=0$ is a removable singular point of $f,$ then $f$ must be analytic and bounded in some deleted neighborhood $0\lt |z|\lt \varepsilon.$

Exercise 1: Find the Laurent series expansion for $g$ and $h$ to confirm that they have removable singularities at $z_0=0.$

Essential singularity

If an infinite number of the coefficients $b_n$ in the principal part (\ref{principal}) are nonzero, then $z_0$ is said to be an essential singular point of $f.$

Examples

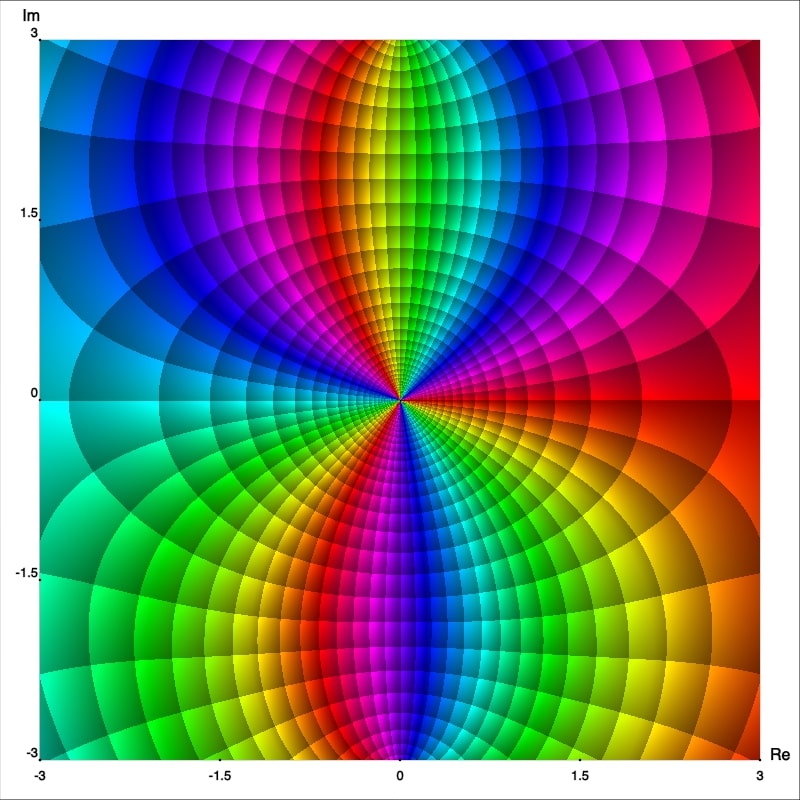

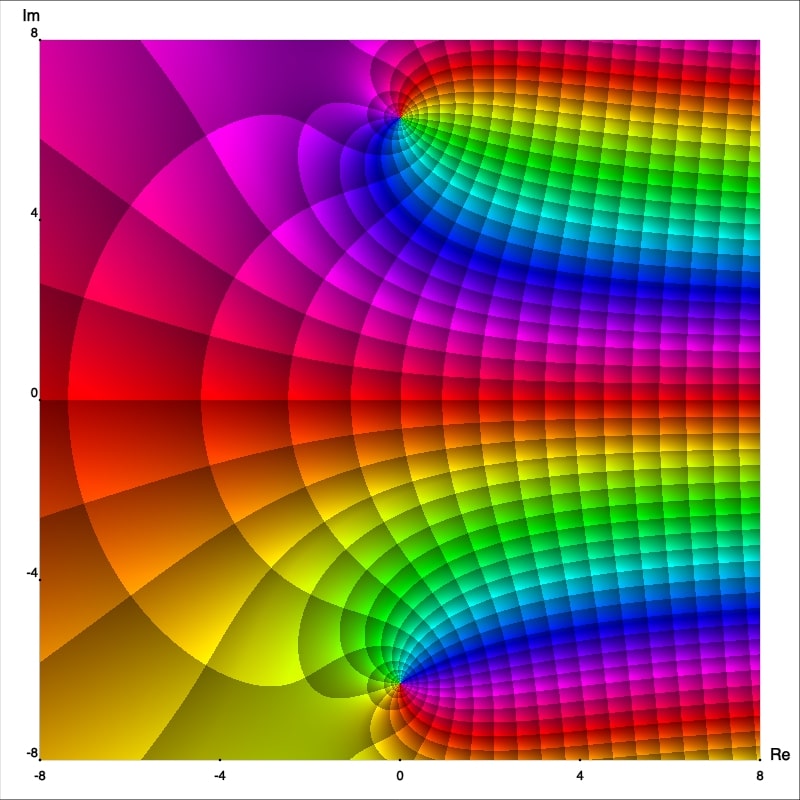

The function $$f(z)=\exp\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)$$ has an essential singularity at $z_0=0$ since \begin{eqnarray*} f(z)&=&1+\frac{1}{1!}\cdot\frac{1}{z}+\frac{1}{2!}\cdot \frac{1}{z^2}+\cdots\\ &=&\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n!}\cdot \frac{1}{z^n}, \quad (0\lt |z|\lt \infty). \end{eqnarray*}

Figure 7 shows the enhanced portrait of $f$ in the square ${|\text{Re }z|\lt 0.5}$ and ${|\text{Im }z|\lt 0.5}.$ The first thing we notice is that the behaviour of $f$ near the essential singular point is quite irregular. Observe how the isochromatic lines, near $z_0=0,$ form infinite self-contained figure-eight shapes.

In fact, a neighborhood of $z_0=0$ intersects infinitely many isochromatic lines of the phase portrait of one and the same colour [Wegert, 2012, p. 181]. This fact can be appreciated intuitively by plotting the simple phase portrait of $\exp(1/z)$ on a smaller region, as shown in Figure 8.

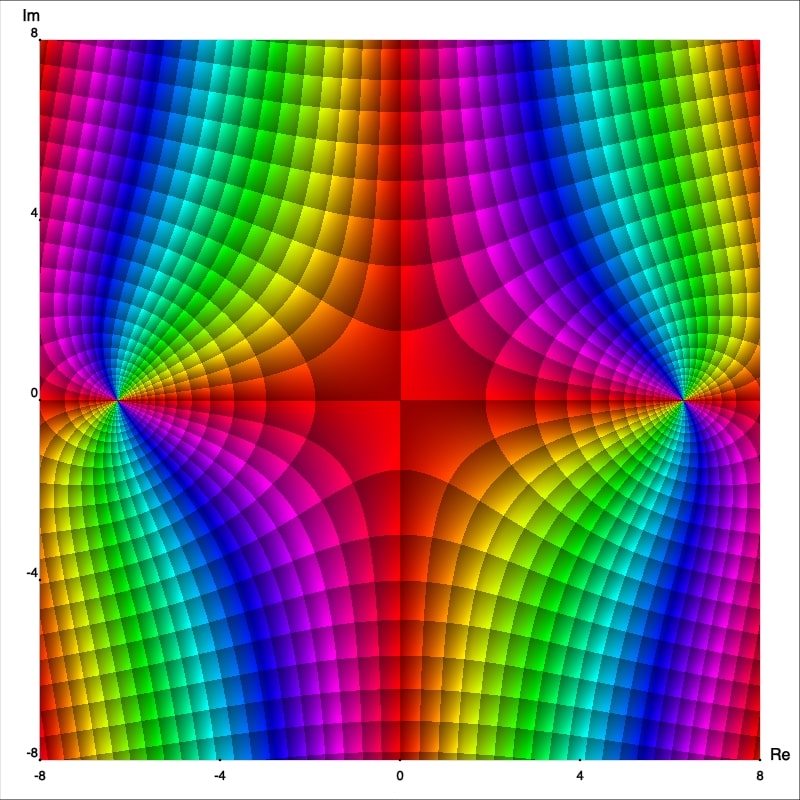

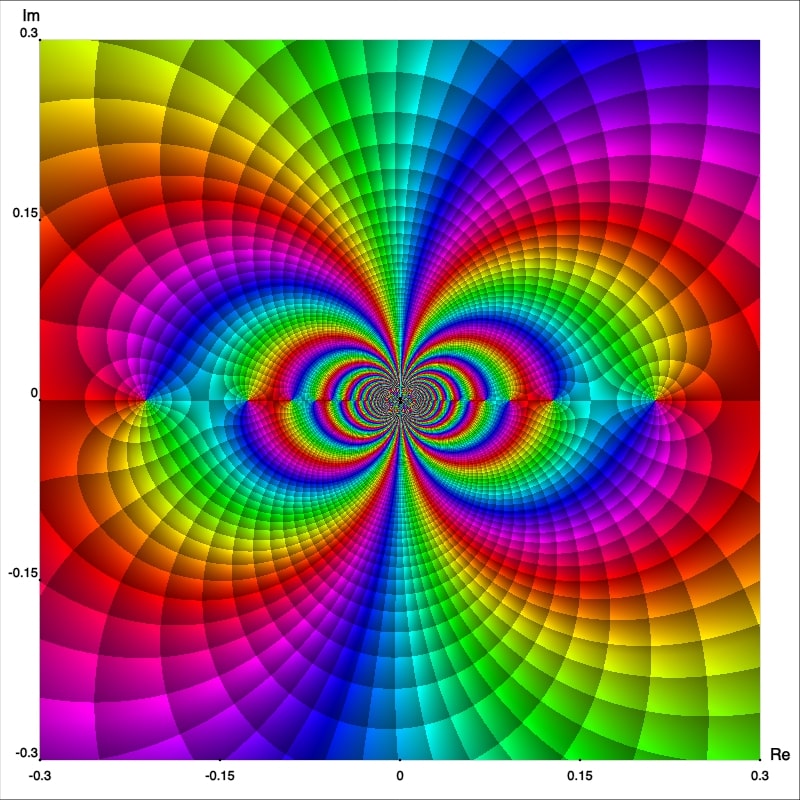

Another example with an essential singularity at the origin is the function $$g(z) = (z - 1) \cos\left(\frac{1}{z}\right)$$ Figure 9 shows the enhanced phase portrait of $g$ in the square $|\text{Re } z| \lt 0.3$ and $|\text{Im } z| \lt 0.3.$

Exercise 2: Find the Laurent series expansion for $(z − 1) \cos(1/z)$ to confirm that it has an essential singularity at $z_0=0.$

Final remark

Phase portraits are quite useful to understand the behaviour of functions near isolated singularities. Figures 7 and 9 indicate a rather wild behavior of these functions in a neighborhood of essential singularities, in comparison with poles and removable singular points. In addition, they can be used to explore and comprehend, from a geometric point of view, more abstract mathematical results such as the Great Picard Theorem, which tells us that any analytic function with an essential singularity at $z_0$ takes on all possible complex values (with at most a single exception) infinitely often in any neighborhood of $z_0.$