Complex Differentiation

The notion of the complex derivative is the basis of complex function theory. The definition of complex derivative is similar to the derivative of a real function. However, despite a superficial similarity, complex differentiation is a deeply different theory.

A complex function $f(z)$ is differentiable at a point $z_0\in \mathbb C$ if and only if the following limit difference quotient exists

Alternatively, letting $\Delta z = z-z_0,$ we can write

We often drop the subscript on $z_0$ and introduce the number \[\Delta w = f(z+\Delta z)-f(z).\] which denotes the change in the value $w=f(z)$ corresponding to a change $\Delta z$ in the point at which $f$ is evaluated. Then we can write equation (\ref{diff02}) as \[\frac{d w}{d z}= \lim_{\Delta z \rightarrow 0}\frac{\Delta w}{\Delta z}.\]

Despite the fact that the formula (\ref{diff01}) for a derivative is identical in form to that of the derivative of a real-valued function, a significant point to note is that $f'(z_0)$ follows from a two-dimensional limit. Thus for $f'(z_0)$ to exist, the relevant limit must exist independent of the direction from which $z$ approaches the limit point $z_0.$ For a function of one real variable we only have two directions, that is, $x\lt x_0$ and $x\gt x_0.$

A remarkable feature of complex differentiation is that the existence of one complex derivative automatically implies the existence of infinitely many! This is in contrast to the case of the function of real variable $g(x),$ in which $g'(x)$ can exist without the existence of $g''(x).$

Cauchy-Riemann equations

Now let's see a remarkable consequence of definition (\ref{diff01}). First we will see what happens when we approach $z_0$ along the two simplest directions - horizontal and vertical. If we set $$z= z_0 + h = (x_0+h)+iy_0,\quad h\in \mathbb R,$$ then $z \rightarrow z_0$ along a horizontal line as $h\rightarrow 0.$ If we write $f$ in terms of its real and imaginary components, that is $$f(z) = u(x,y)+iv(x,y),$$ then $$f'(z_0)= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0}\frac{f(z_0+h)-f(z_0)}{h}.$$ Thus

Example 1: Consider the function $f(z)=z^2,$ which can be written as $$z^2 = \left(x^2-y^2\right)+ i \left(2xy\right).$$ Its real part $u = x^2-y^2$ and imaginary part $v=2xy$ satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations, since $$u_x=2x = v_y, \quad u_y = -2y = -v_x.$$ Theorem 1 implies that $f(z)=z^2$ is differentiable. Its derivative turns out to be

Fortunately, the complex derivative has all of the usual rules that we have learned in real-variable calculus. For example,

and so on. In this case, the power $n$ can be a real number (or even complex in view of the identity $z^n = e^{n \log z}$), while $c$ is any complex constant. The exponential formulae for the complex trigonometric and hyperbolic functions implies that they also satisfy the standard rules

If the derivatives of $f$ and $g$ exist at a point $z,$ then \begin{eqnarray*} \frac{d}{dz}\left[f(z)+g(z) \right]=f^{\prime}(z)+g^{\prime}(z)\\ \frac{d}{dz}\left[f(z)g(z) \right]=f(z)g^{\prime}(z)+f^{\prime}(z)g(z) \end{eqnarray*} and, when $g(z)\neq 0,$ \begin{eqnarray*} \frac{d}{dz}\left[\frac{f(z)}{g(z)} \right]=\frac{g(z)f^{\prime}(z)-f(z)g^{\prime}(z)}{\left[g(z)\right]^2} \end{eqnarray*} Finally, suppose that $f$ has a derivative at $z_0$ and that $g$ has a derivative at the point $f (z_0).$ Then the function $F(z) = g\left(f (z)\right)$ has a derivative at $z_0,$ and \begin{eqnarray*} F^{\prime}(z)=g^{\prime}\left(f(z_0)\right)f^{\prime}(z_0) \end{eqnarray*} Note that the formulae for differentiating sums, products, ratios, inverses, and compositions of complex functions are all identical to their real counterparts, with similar proofs. This means that you don't need to learn any new rules for performing complex differentiation!

Sufficient conditions for differentiability

Satisfaction of the Cauchy-Riemann equations at a point $z_0 = (x_0, y_0)$ is not sufficient to ensure the existence of the derivative of a function $f(z)$ at that point. However, by adding continuity conditions to the partial derivatives, we have the following useful theorem.

Example 2: Consider the exponential function $$f (z) = e^z = e^xe^{iy} \quad \quad (z = x + iy),$$ In view of Euler's formula, this function can be written $$f(z) = e^x \cos y + ie^x \sin y,$$ where $y$ is to be taken in radians when $\cos y$ and $\sin y$ are evaluated. Then

Since $u_x = v_y$ and $u_y = -v_x$ everywhere and since these derivatives are everywhere continuous, the conditions in the above theorem are satisfied at all points in the complex plane. Thus $f^{\prime}(z)$ exists everywhere, and

Note that $f^{\prime}(z) = f (z)$ for all $z.$

A consequence of the Cauchy-Riemann conditions is that the level curves of $u,$ that is, the curves $u(x,y)=c_1$ for a real constant $c_1,$ are orthogonal to the level curves of $v,$ where $v(x,y)=c_2,$ at all points where $f^{\prime}$ exists and is nonzero. From Theorem 2 we have

Consequently, the two-dimensional level curves $u(x,y)=c_1$ and $v(x,y)=c_2$ are orthogonal.

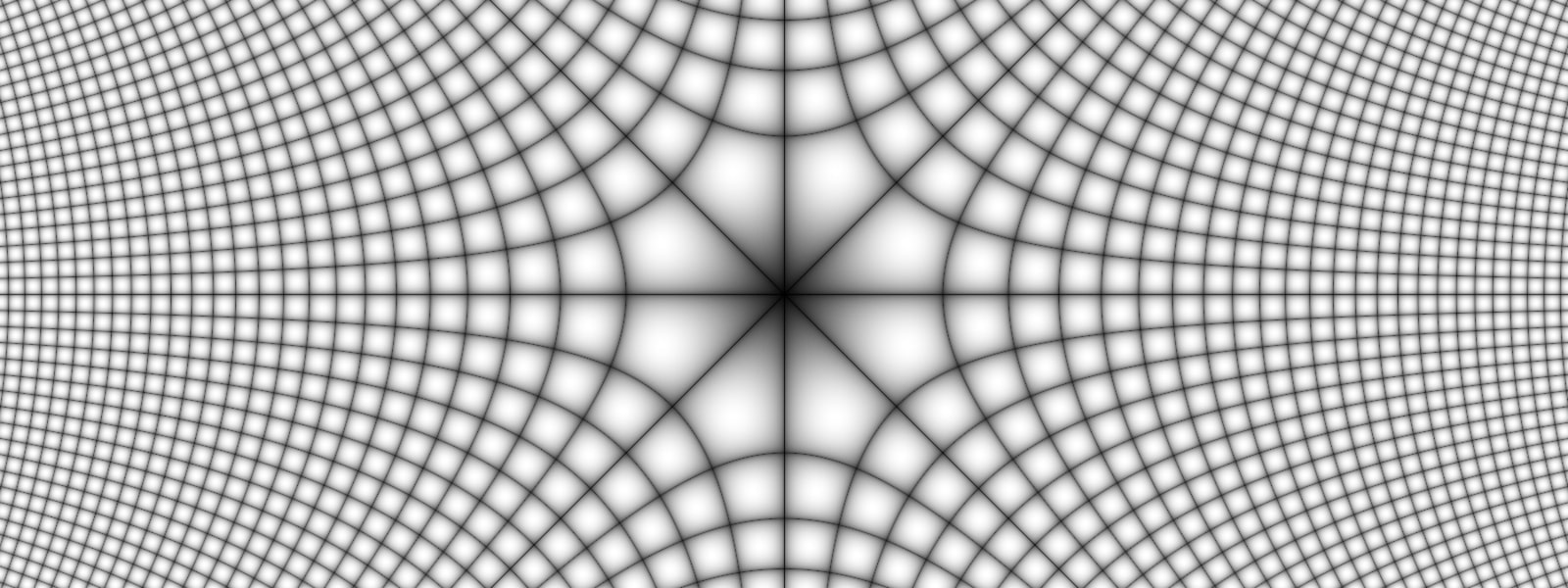

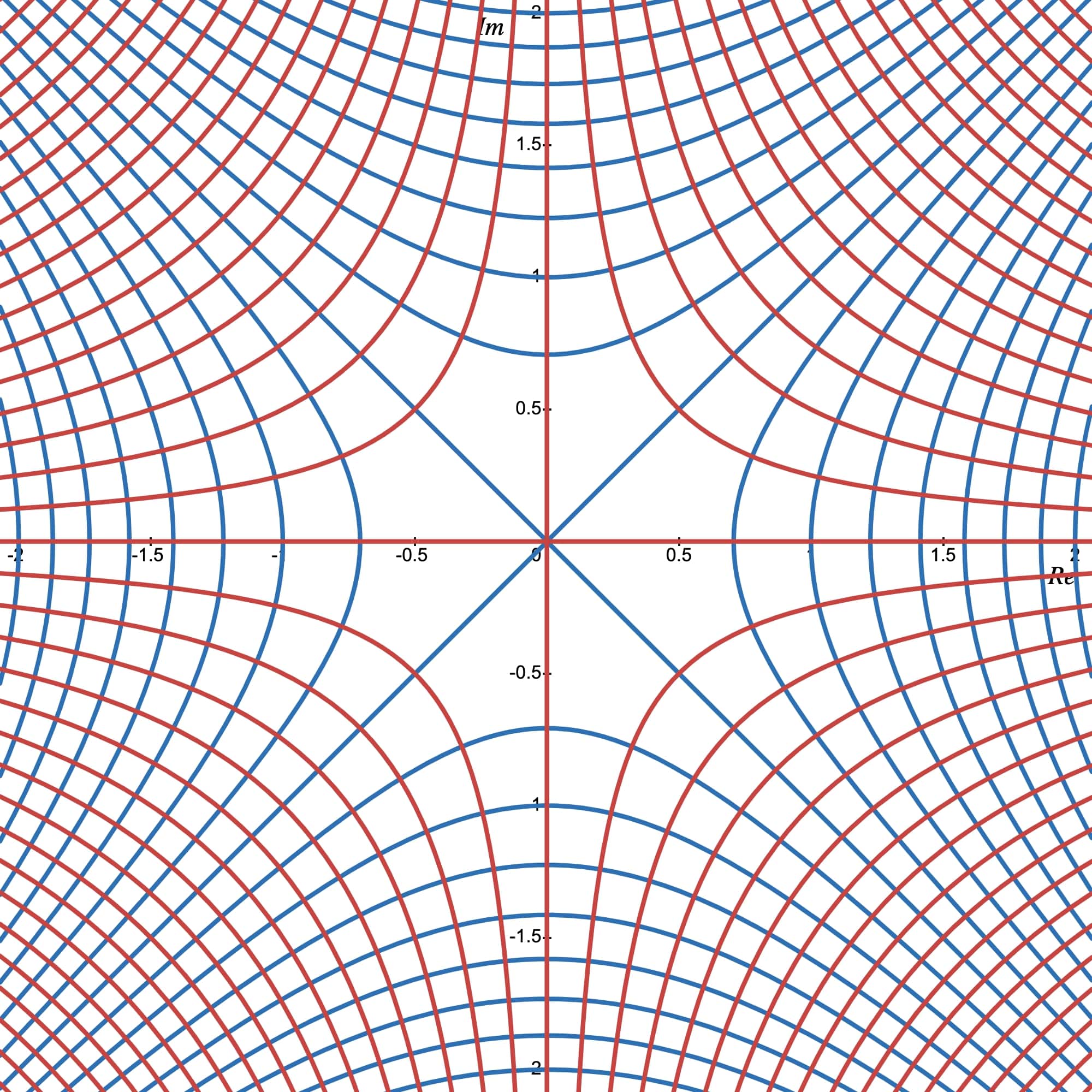

Example 3: For the function $f(z) = z^2,$ the level curves $u(x, y) = c_1$ and $v(x, y) = c_2$ of the component functions are the hyperbolas indicated in Figure 2. Note the orthogonality of the two families. Observe also that the curves $u(x, y) = 0$ and $v(x, y) = 0$ intersect at the origin but are not, however, orthogonal to each other.

Analytic functions

Let $f:A\rightarrow \mathbb C$ where $A\subset \mathbb C$ is an open set. The function is said to be analytic on $A$ if $f$ is differentiable at each $z_0\in A.$ The word "holomorphic", which is sometimes used, is synonymous with the word "analytic". The phrase "analytic at $z_0$" means $f$ is analytic on a neighborhood of $z_0.$

An entire function is a function that is analytic at each point in the entire finite plane. Since the derivative of a polynomial exists everywhere, it follows that every polynomial is an entire function.

If a function $f$ fails to be analytic at a point $z_0$ but is analytic at some point in every neighbourhood of $z_0,$ then $z_0$ is called a singular point or singularity, of $f.$

Example 4: The function $$f(z) = \frac{1}{z}$$ is analytic at each nonzero point in the finite plane. On the other hand, the function $$f(z) = |z|^2$$ is not analytic at any point since its derivative exists only at $z = 0$ and not throughout any neighbourhood.

The point $z = 0$ is evidently a singular point of the function $f(z) = 1/z.$ The function $f(z) = |z|^2,$ on the other hand, has no singular points since it is nowhere analytic.

If two functions are analytic in a domain $D,$ their sum and their product are both analytic in $D.$ Similarly, their quotient is analytic in $D$ provided the function in the denominator does not vanish at any point in $D.$ In particular, the quotient $$\frac{P(z)}{Q(z)}$$ of two polynomials is analytic in any domain throughout which $Q(z)\neq 0.$

Furthermore, from the chain rule for the derivative of a composite function, it implies that a composition of two analytic functions is analytic.

Example 5: The function $$f(z) = \frac{4z+1}{z^3-z},$$ is analytic throughout the $z$ plane except for the singular points $z=0$ and $z=1,-1.$ The analyticity is due to the existence of familiar differentiation formulas, which need to be applied only if the expression for $f^{\prime}(z)$ is wanted. In this case, we have $$f^{\prime}(z)=\frac{-8z^3-3z^2+1}{z^2(z^2-1)^2}.$$

When a function is given in terms of its component functions $$u(x, y)\quad \text{and}\quad v(x, y),$$ its analyticity can be demonstrated by direct application of the Cauchy-Riemann equations.

Example 6: The function $$f(z)=e^ye^{ix}=e^y\cos x +ie^y\sin x$$ is nowhere analytic. The component functions are $$u(x,y)=e^y\cos x\quad\text{and}\quad v(x,y)=e^y\sin x.$$ If $f(z)$ were analytic, then (using Cauchy-Riemann equations)

Another useful property what we will use later is the following: